One of the first things Dr. Fisher told us on the first day of Phage Hunting was that this class would not be a typical one. She warned us that we would have to get used to having people at multiple different stages, and come to accept the fact that not everything follows a perfect timeline or goes according to plan.

How many times have you heard “you learn from your mistakes,” or, “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger”? These phrases just seem like mindless clichés that people say when they can’t think of anything else. But let me tell you, this class has more than proven to me that failure is not a reason quit.

Going through direct isolation, plaque assays, serial dilutions, and enriched isolation, all of which resulted in absolutely no plaques, was discouraging to say the least. Especially because I was told multiple times that it’s nearly impossible not to get results from an enriched isolation, due to the fact that the 7H9 amplifies the phage in the sample. Despite this, I am a very determined person, and I wasn’t ready to adopt someone else’s plaques, so I decided that I would try an enriched isolation with one last new soil sample; this would be my fourth sample.

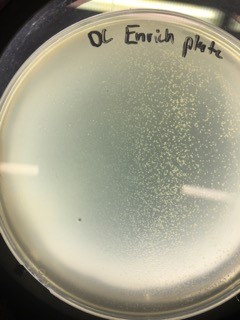

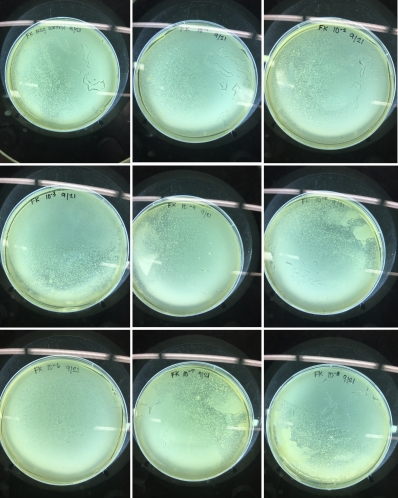

This is pretty much what all my plates came back looking like up to this point: wonderfully plaque-less lawns of smeg.

For this last attempt, I told myself I would follow the procedure to the T, and take my time making sure I was doing each step correctly. But right from the get-go, something had to stray from protocol. We didn’t have enough 7H9 in the lab, so each student got only 10ml of enrichment broth instead of the suggested 20ml. Since enriched isolation hadn’t worked for me when I had the correct amount of it, I was not confident that it would work this time with half the amount. Despite this, I was determined to keep a positive attitude, and carry this last effort to the end.

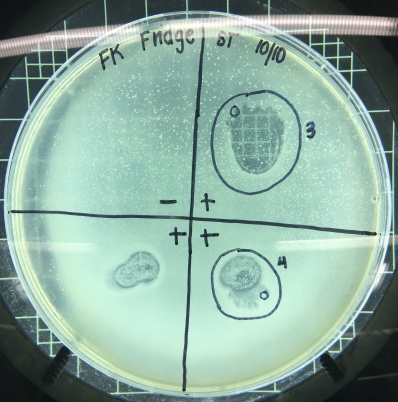

After I’d finished filtering my sample, I handed off the conical tube containing the filtrate, thinking it was going into the incubator. The next lab period I went to get my sample from the incubator, but I could not find it. It turned out that my filtrate had actually been in the fridge for the last 48 hours. So, at this point, it pretty much felt like my experience in this class was a real-life embodiment of Murphy’s Law, which states that “anything that can go wrong, will go wrong.” What’s interesting is that the plaque I ended up choosing actually came from this “fridge” sample.

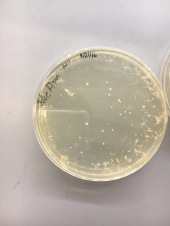

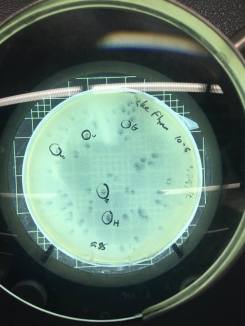

I decided to do a spot test right away with the filtered enrichment culture I’d obtained from two separate filtration procedures to make sure there was phage in this sample that was capable of infecting smeg as a host bacteria. The next lab period, when I checked the results of the spot test I could not believe my eyes. I’d gotten so used to seeing full lawns of smeg that it took me by surprise when I actually saw the circular clearings I’d been waiting for for weeks.

Phinally!

Plaques on plaques on plaques

I’ve only been in Phage Hunting for a matter of weeks, but I’ve already become familiar with a variety of research techniques (of which I knew absolutely nothing about before taking this class), I’ve learned more about the world of bacteriophages, and I’ve come to understand more about the nature of research. But, perhaps the most important thing I’ve learned from this course (besides how to do aseptic technique like a boss) is that achieving success after rounds of failure is sometimes more fulfilling than success that comes without any obstacles.